[Updated essay posted below]

Dear Timo,

Life and my head are fragmented at the moment – not so much in a bad way, but: week 10 teaching semester with anxious honours students, one month in new house and still among boxes, three deadlines this week and so on. Therefore, this month’s bird offering reflects this mild chaos – in Australian colloquialism (which is relevant, as you will see) a dog’s breakfast of an offering. Or, as my dad used to say: all over the shop like a mad woman’s breakfast. Or a toddler’s breakfast, which is also on point this morning.

I will revise this one at a later date – it lacks colour (literally).

A hope you are well and less chaotic than me this month, and less busy than you last month. Love to George too, so excellent to see him robed up for his graduation, and you there in your Santa outfit.

xxx

Updated essay, November 2019:

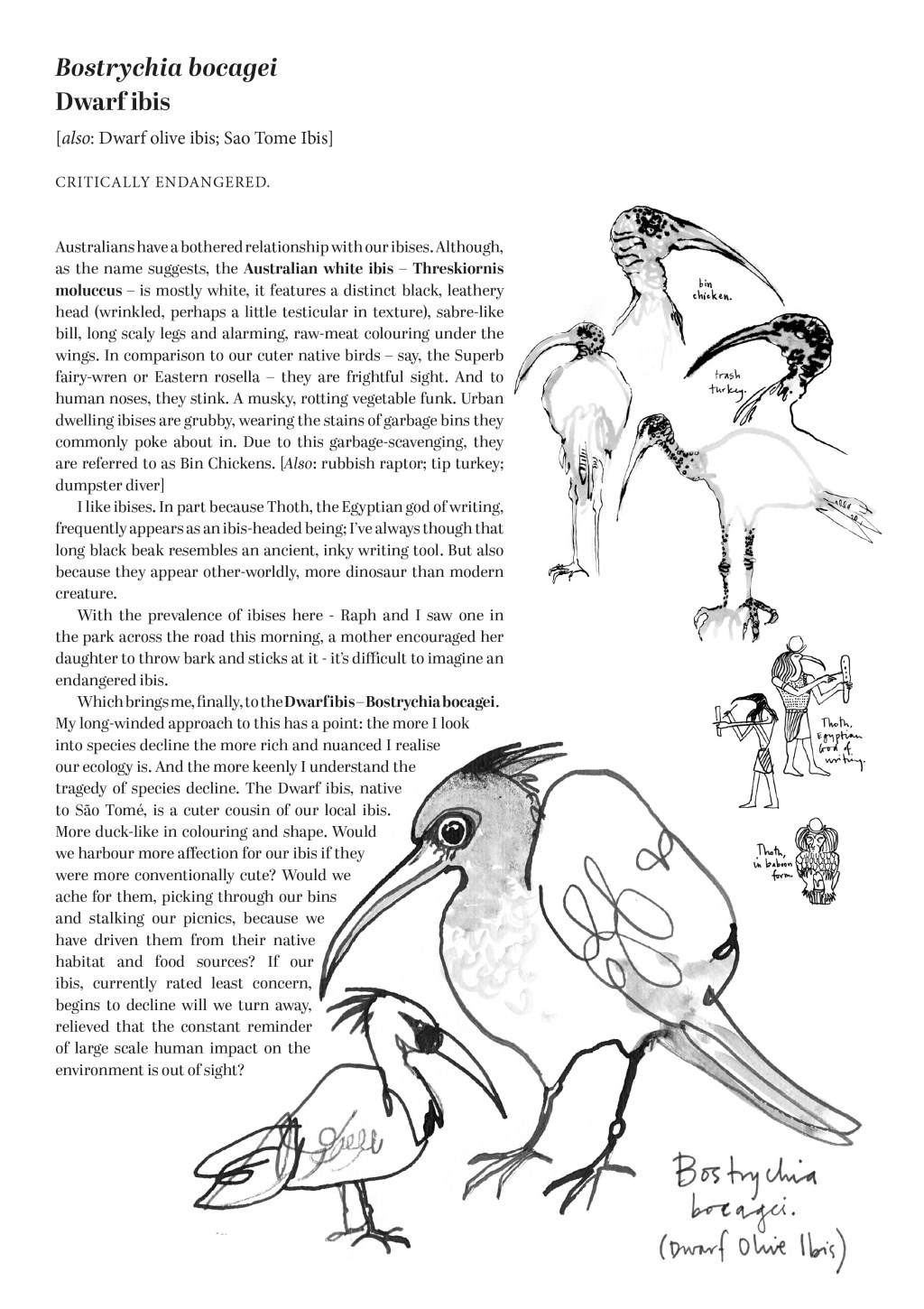

Australians have a bothered relationship with our ibises. Although, as the name suggests, the Australian white ibis (Threskiornis moluccus) is mostly white, it features a distinct black, leathery head (wrinkled, perhaps a little scrotal in texture), sabre-like bill, long scaly legs and alarming, raw-meat colouring under the wings. In comparison to our cuter native birds – say, the Superb fairy-wren or Eastern rosella – they are a frightful sight. And to human noses, they stink. A musky, rotting vegetable funk. Urban dwelling ibises are grubby, wearing the stains of garbage bins they commonly poke about in. Due to this garbage-scavenging, they are referred to as Bin Chickens. [Also: rubbish raptor; tip turkey; dumpster diver; picnic pirate; sandwich stealer]

I like ibis. In part because Thoth, the Egyptian god of wisdom, knowledge and writing, frequently appears as an ibis-headed being; that long black beak resembles an ancient, inky writing tool.* But also because they appear other-worldly, more dinosaur than modern creature. Birds survived the fifth mass extinction – the meteor impact best known for wiping out the rest of the dinosaurs – but are not faring well in the sixth extinction, in which humankind is wiping out our furred, scaled, feathered kin.

*Until the 1990s, the African Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) was classified as the same species as the Australian White ibis. Yet instead of being reviled, the African sister-species is revered in Eygptian culture. Beyond the ancient association with Thoth, they played a key role in keeping river water clean and usable for humans. A companion species, rather than a pest. Although globally categorised as Least Concern, the sacred ibis has been extinct in Egypt since around 1850. Archeologists have uncovered tombs with up to 4 million mummified ibis at a single site, which current researchers believe were wild caught (rather than bred for purpose). If nothing else, this demonstrates the previous abundance of the species.

With the prevalence of ibis here – Raph and I saw one in the park across the road this morning, a mother encouraged her daughter to throw bark and sticks at it* – it’s difficult to imagine an endangered ibis.

*I’ve negotiated with Raph that it’s not ideal but ok to chase birds, but never to throw things or yell at them. The nearby ‘urban farm’, where we sometimes eat because it allows kids to go free-range on the lawn, had to remove the coop of egg-laying chickens because kids were throwing rocks at them. I didn’t realise Raph overheard this conversation until a day later when he asked why kids would throw rocks at the chooks. I couldn’t answer him. So, as 3-year-olds do, he asked the question over and over, for days, until I could give him a satisfactory answer, or another question worried him more. I can’t remember, but it was probably the latter in this case. I hope I didn’t reply ‘those kids may grow up to be serial killers’, but it crossed my mind.

Which brings me, finally, to the Dwarf ibis – Bostrychia bocagei. My long-winded approach to this has a point: the more I look into species decline the more rich and nuanced I realise our ecology is. And the more keenly I understand the tragedy.

The Dwarf ibis, native to São Tomé, is a cuter cousin of our local ibis. More duck-like in colouring and shape, it was last assessed in 2018 as critically endangered. The population size is unverified (insufficient data) but classified in the band of 50 – 249 mature individuals, and thought to be decreasing due to opportunistic hunting (bonus kills for hunters pursuing pigs), agriculture-induced habitat loss, and introduced predators such as the Mona Monkey. It is possible these birds will disappear in my lifetime.

Would we harbour more affection for Australian white ibis if they were more conventionally cute, like their African cousins? Would we ache for them as they pick through our bins and stalk our picnics, refugees driven from native wetland habitat and food sources by drought and agriculture? If our ibis – currently classified Least Concern – begins to decline will we turn away, relieved that this constant reminder of large-scale human impact on the environment is out of sight, or feel guilt for what we have passively born witness to?

Yet Australians love an underdog; the iconic little Aussie Battler. In 2017, the ibis came a narrow second to the magpie in The Guardian newspaper’s annual ‘bird of the year’ campaign. It was later reported that “the competition was complicated by attempted vote-rigging, drama and political intrigue.” Investigation into a suspicious number of votes for the powerful owl resulted in a significant number of votes to be removed. In addition, there was much Twitter twatter over the course of the three-week campaign, much of it centred around the white ibis, including a #TeamBinChicken tag adopted by federal politician Scott Ludlam. One tweeter asked “Is the Ibis the spirit animal of Australian millenials?”

In a 2018 essay published in The Conversation (and republished by several mainstream news platforms), Paul Allatson and Andrea Conner report that the white ibis has ‘gone viral’ in popular culture, citing a proliferation of ibis-adorned items for sale online, ibis murals popping up in major cities around the country and even a trend for ibis tattoos: “This ibis juggernaut says a lot about Australian identity and culture in the 21st century — and human-animal relations in a time of environmental threat and uncertainty.” On the flip side, they do note that in 2016 almost 8,000 people registered for International Glare at Ibises Day, which encourages people to “gather in your local park and glare and show general distaste towards ibises”.

Allatson and Conner conclude that native white ibis are tenacious and fearless ‘environmental refugees’, reminding us of the environmental challenges we face: “Ibis have infiltrated our daily speech and our cultural consciousness. Indeed the ibis is fast becoming the new animal totem for thinking about the very idea of ‘Australia’ today.”

Although not officially sacred, perhaps the white ibis is an ideal totem animal – resilient and capable of, to borrow a complex idea from Donna Haraway, ‘staying with the trouble’ of our current environmental crisis.

[See also The Wilderness Society’s berserk ‘Save Ugly’ campaign]

Leave a comment